Alzheimer's is like trying to describe air.

My previous attempt to write about Thomas DeBaggio's Alzheimer's memoir, Losing My Mind: An Intimate Look at Life with Alzheimer's (The Free Press, 2003), netted a collage poem rather than an essay, here. That poem collages the words of DeBaggio with lines from George Oppen's late poems; reading the memoir offered me access to the Alzheimer's in Oppen's writing, especially since DeBaggio's bad dreams so mirrored Oppen's. But now I'd like to look at Losing My Mind more critically, in the third part of a sequence, "The problem with Alzheimer's narratives." Part one is here; part two there. (Digression: Bryant asked me if I would write three blog posts on this subject, to which I responded that I was going to argue for chaos in a neat three part dialectic! Today is synthesis day at Tinfish Editor's Blog.)

My argument, so far, is best distilled in reading Rachel Hadas's reading of Emily Dickinson's poem, containing these lines: "Ruin is form--Devil's work / Consecutive and slow-- / Fail in an instant, no man did / Slipping--is Crash's law." In that last post, I wrote that, "Hadas reads this poem as capturing "the theme of the extreme insidiousness of the loss" [of dementia]; what strikes me is that the "failure" of the rhyme (deliberate as it may be) evokes insidiousness rather than merely conveys it." It's the difference between language and form as conveyance and as evocation that's at the heart of my argument about Alzheimer's narrative. While most such narratives convey from the point of view of the child or partner of the Alzheimer's patient what it means to live with the disease, I'm arguing for narratives that evoke the illness for the reader.

In a 2003 essay, "Looking back from loss: views of the self in Alzheimer's disease," Anne Davis Basting notes that "There are only a handful of published texts in which the primary author is the person with the disease" (88). Thomas DeBaggio's is one of these, published at nearly the same time Basting was writing her article about several other such narratives. DeBaggio was a journalist, one obsessed with the craft of writing, so his memoir is as much about writing as it is about his disease. Since there is no separating this disease from thinking, writing and illness dovetail in amazing passages about the difficulty of writing through Alzheimer's.

DeBaggio divides his book into three sections; these sections weave together, rather than move in linear sequence. He explains them in the Author's Note. "I call the first narrative the Baby Book," he writes. This is the repository of his long-term memories from early childhood until the early 1970s, or some 20 years before he began writing this book. "A second narration intersects the first, relating stories of humiliation and loss." This narrative occurs in the present, which is full of "memory lapses and language dificulties [sic]." It also occurs in italics, and is more meditative than the other sections. The third narrative is factual, relates the results of recent Alzheimer's research. He ends the note by noting, "All this is mixed together, as it is in the brain, and follows a pattern of its own" (xi). What he does not say up front is that the book also repeats itself. The Discussion Guide's question number 6 seems disingenuous, when it asks the reader: "Losing My Mind has passages that are repeated at times, particularly in the second half. Do you think this is intentional?" (212)

Or maybe it's only half-disingenuous, because it's here one senses that the book comes to us from both an author and an editor who work at common and sometimes at cross-purposes. The repetitions, which come to us toward the end of the book, sound like odd echoes, except they require a new term, since echoes can be heard as repetition, whereas Alzheimer's repetitions cannot. A writer who hears her own echoes edits them out. At the moment when DeBaggio repeats the story of finishing Catcher in the Rye as an airplane lands, then "looking for 'phonies' and easily [spotting] them tangled in their insecurities," we witness this repetition-effect-affect. It causes the reader confusion at first: why am I hearing this sentence or paragraph again? What could it mean? Does it mean anything? Like the author himself, we are searching our minds for something that may or may not be there. We rifle through the book looking for the repetition; it becomes something that we've (if only momentarily) lost. Back on my figurative feet, I wonder what role the editor played in this: were these Alzheimer's echoes in the original text? Are they staged to perform Alzheimer's? Does it matter? How many such repetitions were admitted into the final text, how many removed? How strong an effect was the editor willing to permit in the book?

I admire the publisher for including these lapses-that-are-not-lapses but integral moments in the illness. But I wonder about the rest of the text; even as DeBaggio devotes a lot of time to inventorying his difficulties in writing, the book is largely "clean" of error. Here are just a few moments where he remarks on his problems in writing:

I am being gobbled up in time. The words are under control but the letter that form the words squirm in their own directions. (20) (italics his)

Words slice through my mind so fast I cannot catch them and marry them to the eternity of the page. (27)

[And less grandly, not in the italics that indicate the wisdom stream of the book:]

Writing sometimes becomes difficult. Words vanish before they reach the page. Most of the time the biggest drawback is my plummeting typing accuracy. So far there are few words the spell checker cannot correct. (31)

My ability to remember words is diminishing rapidly and I can often see the subject but its name eludes me, and this makes me angry and frustrated. (73)

I have just spent five minutes struggling to spell the word "hour." (105)

More and more I am unconsciously mixing words that have similar sounds: our and out, would and wood, me and be, to name a few. This leaking alphabet of reality is something I might have expected in speech, not in writing. (181)

Almost every minute of the day is destroyed by the struggle to reclaim lost words in my search to communicate. It is a losing battle, but I will sing until no word is left. Alzheimer's is making me mute. (187)

The struggle to find the words, to express myself, has become insurmountable. I must now be done with writing and lick words instead. (207)

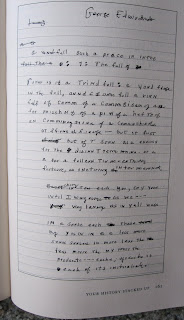

While the repetitions folded into the text, unannounced as such, evoke the Alzheimer's effect, other effects are only announced. As Basting writes about another Alzheimer's memoir, "Although [Diana Friel] McGowin describes the symptoms of Alzheimer's, she does so in language cleansed of the disease--spelling, grammar, and memory of dialogue and events are pristinely intact" (89). While I want to think that the misspelling of "difficulties" in his Author's Note ("memory lapses and language dificulties") is left in to acknowledge the difficulty, I suspect that this is an ordinary typo (the book's own dementia, which it shares with every other text I've ever read!). For the rest of the book is free of the disease. What are typos to us--mistakes, in other words--are intrinsic functions of the illness. They are not mistakes; they are worse than mistakes. They bear witness to a mind's self-loss. The one page of George Edwards's handwriting that Rachel Hadas offers us is worth a hundred pages of typo-free text about the author's problems spelling words! This is where I want to tell the editor to edit less, let in more of the dificulty [sic].

Susan Howe and others have written eloquently about Puritan women's testimonials, which were edited, hence altered, by male ministers. Emily Dickinson's wild texts were weeded and presented to the reader as lawns by male editors (the metaphor is mine). According to Susan Howe: "The issue of editorial control is directly connected to the attempted erasure of antinomianism in our culture. Lawlessness seen as negligence is at first feminized and then restricted or banished" (quoted in Schultz 148). Substitute the word "Alzheimer's" for "antinomian" and you have the argument I want to make here. (That Alzheimer's is largely a disease afflicting women--those who live longest--renders Howe's argument more uncanny yet.) While there's certainly a difference between religious awareness and illness, both their effects are strong, need to be presented "faithfully" in published texts. Do not edit out what makes Alzheimer's texts most powerful, most illustrative of the disease. Leave us undemented readers to struggle with the words, as the writer himself did. If it took DeBaggio five minutes to remember how to spell the word "hour," then it should take us time to read his dificulties, too. Making it easy to absorb DeBaggio's text does not offer us anywhere near a complete picture of what it meant for him to compose it. Absorption, as Charles Bernstein put it in a very different context, is artifice.

To hide Alzheimer's bad spelling is to hide Alzheimer's. And that's what our culture does. It puts sufferers in "homes" or leaves them in their houses to sit by themselves. Very few of us, unless we have relatives with Alzheimer's, are allowed to see the real, if altered, people who suffer from this illness. There are real walls between us and them. And then there are the editorial walls. They're just doing their jobs, I know, those editors. But sometimes the better course is to leave be. Let be be finale of seem, or seam, or seme.

Most Alzheimer's sufferers will not write a book; most of them will not leave the single, profound page that Edwards left for his wife to publish in her memoir. So the discussion I've just had about editing doesn't generally apply to Alzheimer's narratives. Most are and will be written by the well, the witnesses instead of those with the illness. Most will not evoke the illness's effects by using the authority of the "I" (first person knower) to describe it, even if that "I" is losing its authority day by day, page by page. So what then? How are the rest of us to write about Alzheimer's? How can we evoke rather than merely convey our experiences of the illness? And here I begin to repeat myself, as I've addressed this question elsewhere on this blog, and in Dementia Blog and Old Women Look Like This. (Somewhere in the thicket is this post.) And in that post is the kernel of the argument I'll deliver at the Brunel conference in early April, namely that "linear, diachronic narrative strategies assume a logic that the disease has already destroyed, and that we need to use other forms to get at the illness's chaotic thinking."

Appropriately, then, the argument I'm looking for has already happened, over and again, in this space. To find it, I have to hunt back through many posts over the past two or three years. But arguments, like memoirs, are noisy things. And the real crux of the Alzheimer's problem is not its noise, but its silences. When I wrote to Ben Friedlander recently to ask where to find Emerson's dementia in his late work, he responded "@Susan: the two-volume Library of America edition that came out a few years ago is by far the best abridgment. But I occasionally check out the Harvard volumes for browsing, not to mention the notes. The dementia registers in silence: there is very little writing from the last years. Apparently the manuscripts of the late essays--which he couldn't finish on his own--include numerous and sometimes extended repeated passages, which is perhaps the best testament to what was going on. I'd like to see a transcript." There's silence from Emerson, and then there's the other telling silenc(ing), by editors--the helpers who finished for him--removing the repetitions, cleansing the text of his and its illness.

Silences, repetitions. Silenced repetitions. The Alzheimer's sufferer's repetitions are cleansed; the memoirist (like Franzen, like Hadas) leaves them out, writes over them, corrects their spelling. What I want to see are the writings of Alzheimer's sufferers as they were actually penned or pencilled or pixilated. What I want to see from the rest of us is an awareness that our confusions cannot be fixed through narrative or by way of poem. That we need to find a way to evoke these confusions, rather than solve them, or merely convey them. The conveyor belt of narrative has wonderful purposes, yes, but we need to put the knife to it. The Alzheimer's belt has broken. Our stories need to, too.

[The headnote is by Thomas DeBaggio; I'm saving the "click to look inside" from the amazon.com page for its many resonances]

Sources

Anne Davis Basting, "Looking back from loss: views of the self in Alzheimer's disease," Journal of Aging Studies 17 (2003) 87-99.

Susan M. Schultz, A Poetics of Impasse in Modern and Contemporary American Poetry, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.