I was seated at my computer yesterday, tasked with preparing a first class for my graduate workshop in poetry, when an email popped up from the marketing manager of the corporation that runs my mother's Alzheimer's home. SUBJECT: dementia blog. It was a request for me not to use the names of the residents of my mother's home: "Frequently our patients and families blog about their stay at our centers. However, we must comply with HIPAA regulations. When we notice that other patient's names are mentioned, we ask that you edit any identifiable information out of your blog. That can include names, their hometowns, etc." She added that it was acceptable to "limit access" to the blogs that relate to "health care." I have since reduced each resident's first name (which is all I provided in any of my blog entries) to an initial, although I've not removed New York City, or even the Bronx, as the hometown of one woman (even as she sometimes thought it was Paris).

A few questions emerge from this request. If the care home needs to comply with HIPAA regulations, do I, as a writer, need to do so? First, what are these regulations?

The HIPAA Privacy Rule establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other personal health information and applies to health plans, health care clearinghouses, and those health care providers that conduct certain health care transactions electronically. The Rule requires appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of personal health information, and sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures that may be made of such information without patient authorization. The Rule also gives patients rights over their health information, including rights to examine and obtain a copy of their health records, and to request corrections.

Does this presuppose that everything that happens in an Alzheimer's home is health-related? Certainly, Alzheimer's (like schizophrenia, like brain cancer) is a disease, but does that mean that everything a sick person does is strictly private? The stakes are higher when people are unable to give permission of their own accord, I realize, but is my invasion of their privacy, if that is what it is, inevitably detrimental to them? Where does maintaining their privacy and that of their family become yet another way to hide our shame at what so many of us are becoming?

I google "use of proper names in creative non-fiction," which is one of the several genres I am traveling in. I find my former summer colleague, Lee Gutkind, offering this advice, in a piece entitled "How to Stay Out of Trouble":

While the people and places mentioned in creative nonfiction pieces are still around, writers often change the names of characters in their work to avoid conflict. As long as it doesn’t impact the story, changing Linda, the waitress at the Burger Barn, to Cynthia from the Hamburger Hut might save Linda some awkwardness. And if you’ve fudged the facts about her, changing Linda’s name just might save you from a lawsuit, but there is no guarantee. Linda can still sue you for defamation if she is obviously defamed, regardless of the name you give her in the book. Changing a person’s name is not a guarantee of protection, but it might help.

So, you can change names to stay out of trouble, but that may lead you to getting in trouble anyway. What's at stake here seems to be "defamation" and saving someone "from awkwardness," in case you have defamed them. Gutkind continues by advising the writer to ask permission to use names:

Protect yourself by getting written permission from people you wish to write about. And if they are no longer living, make sure you aren’t setting yourself up for a lawsuit from their family. (Obviously, you are fairly safe in writing about people who died long ago.)

So, while The Rule is written to protect the person being written about, here we see the writer advised on how to protect herself. It seems there's trouble everywhere in this non-fiction world. So much that one could probably write a damn good piece of fiction about it!

While I have reduced the residents' names to initials, I would like to explain what I think is at stake in writing seriously about dementia. This meditation returns me to consideration of the public / private binary that came up before in my writing about the alphabet. In our culture, health issues (and everything that emanates from them) are considered private. We all know that those protections are important, but to what extent do some of those protections also hurt us? If the Alzheimer's home, which is already locked-down so that residents don't escape and unwanted strangers can't get in, is considered a zone of privacy, then hasn't "privacy" become another version of "hiddenness." The madwoman in the attic was heard but not seen; the residents of an Alzheimer's home are neither to be heard nor seen. They are safely "put away." Individual family members can and do take their relatives out for a spin on occasion, and there are group field trips once in a while, but for the most part what happens in an Alzheimer's home stays in an Alzheimer's home.

In writing about dementia, I want to pull back that curtain. Any curtain so pulled back reveals a mirror. (That I don't take pictures of any residents except my mother suggests a paradox best considered later.) For what I find most powerful in the Alzheimer's home is not a group of people who are unrelated to us in their behaviors. (I once told a group of people that dementia was like a neutron bomb, was duly chastised by an older woman for not acknowledging the humanity of the dementia sufferer, and have been sensitive to that mistake ever since.) A person with dementia has fewer behaviors than those of us without, but the behaviors that remain are hardly alien to us. The woman who wants to go home; the man who calls out a woman's name; the woman who sings loudly and off-key; the mother who weeps for a baby; these are familiar (familial) activities. While their dysfunctional behaviors emanate from a severe illness, that illness does not strip away their relation to those of us who are "healthy." In some ways, it increases the pathos of that relation. The privacy we demand asks us not to look in the mirror, but only at the curtain. Excuse the Romantic tropes here; I hope not to be using them according to Romantic theories, but in a more literal sense. They act like us, we like them.

But why my stubbornness about names? Yes, the waitress named Linda might easily be transposed to the waitress at a similar restaurant with another ordinary, mid-20th century name. If the writer is out to defame Linda, who yelled at her child when the child spilled her ice water, then perhaps the writer needs some protection from the Linda who has not protected herself with due patience. But if Linda is in an Alzheimer's home, where her sole possessions are a few family photographs, some clothes, a handbag and her name? Easy enough to change the name, but I would argue that there are good reasons also for keeping it. To change a name is to create a secret, open or shut. To change a name is to change an identity (when I see a Linda in my mind's eye, she's not a Cynthia). When I hear the name Susan addressed to someone other than myself, I know I'm in the neighborhood of a woman born in the mid-50s to the mid-60s; our name is a generational marker. Maybe if I changed than name to Janet or Ruth, it would have a similar resonance. But leaving the name alone, in the context of the Alzheimer's home, is an assertion that something of this person remains as it was. And, that if that person is now unrecognizable as "herself," she is still related to that earlier person in ways stronger than just the body.

The Alzheimer's home is characterized by a deliberate and irrevocable blandness. My mother's house contained something of that blandness; it participated in the suburban school of interior decoration, after all. But the generic quality of the "home," its furnishings, its art, its use of language ("have you ever been in a boat?" beside a picture of The Constitution), while they aim to provide calm for residents and/or their relatives, also provide some cover of secrecy. If these residents are no longer individuals, in the sense we usually intend that word to mean, then their surroundings must also fail to stick out. I have only been in two Alzheimer's homes, but their similarities were striking. Blandness is a form of control for both the suburban resident and the resident of the Alzheimer's home; only the scale seems different.

Doubtless I protest too much, make philosophical hay out of the act of courtesy that was asked of me. But much of what we keep secret (illness, weapons systems) protects us only briefly, and often fails to protect those around us. We try to protect ourselves from knowing that people grow old--too old--that they lose their "right" minds, that to spend time with them can be quite painful. We lock their doors and we lock away their names.

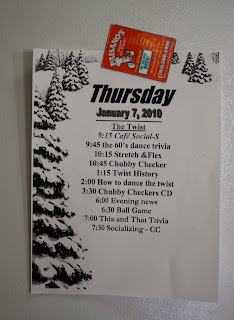

[The images are from my mother's Alzheimer's home in Fairfax, Virginia]

4 comments:

http://jonathan-morse.blogspot.com/2010/01/privacy-and-memory-exchange-with-susan.html

Your last line struck me.

"Country Lane"

"In Arden Courts"

Sounds like a JA book! :)

Congratulations and keep up the good words and works, Anny

The Rule requires appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of personal health information, and sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures that may be made of such information without patient authorization.

I share your instincts completely, indeed a sense of shock at the restriction you encountered. Who does the privacy benefit? I think indignantly. But I'll go on thinking about this, because of the counter-question, Who does the publicity benefit?

Post a Comment